Science and art combine to convey wildfire's effects

December 14, 2017

Frederick Freudenberger

828-674-6119

University of Alaska Fairbanks scientists are presenting their work at the American Geophysical Union Fall Meeting in New Orleans this week. Here are some highlights of their research, as shared at the world’s largest Earth and space science meeting.

The American Geophysical Union Fall Meeting is the perfect place to showcase new scientific ideas and research. And as science becomes more interdisciplinary, so does the meeting.

Peter Webley, associate research profesor at the UAF Geophysical Institute, on Dec. 12 presented his work in a new AGU series that blends science with art. The presentation combined wildfire imagery with originally composed music and animations to illustrate fire's landscape effects.

“Music helps make you feel the larger heartfelt impact that the fire can have," Webley said. "Music helps you feel very differently about the images than if you were just looking at them."

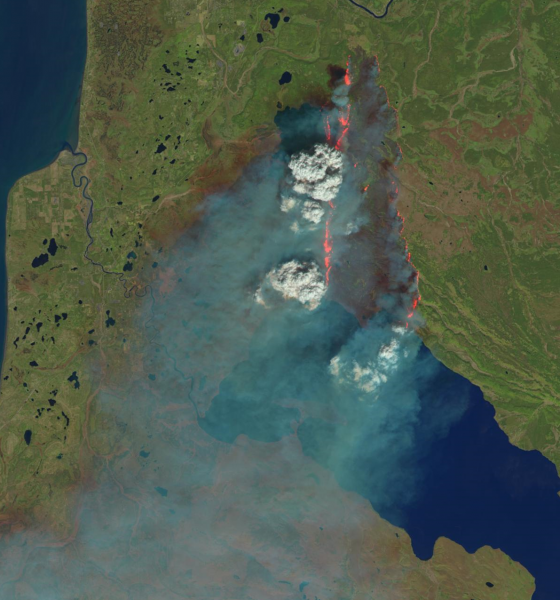

Webley, who researches use of remote sensing imagery to monitor and map natural hazards, started with satellite imagery of wildfires from Alaska, California, Washington and Oregon. Co-author Trevor Adams, orchestra director at West Valley High School in Fairbanks, then composed original music to accompany them and encourage an emotional response. Co-author Jill Shipman, a doctoral student and UAF FRAME production manager, brought the team together and designed the multimedia storytelling.

“A lot of what we are talking about is the process. How do you move geoscience data and artistic interpretation and presentations together? A lot of geoscientists don’t think like an artist, and a lot of artists don’t think like a geoscientist,” Webley said. “How do you take sometimes static images or animations of images changing, put a musical piece on top and then make that interesting to the audience like a piece of art?”

The work is part of a new series at AGU called eLightning Presentations, interactive electronic posters designed to encourage visibility and engagement with the audience. Shipman is the lead convener of the session.

“I want to broaden the definition of what the intersection of art and science is to show that there is no one way to approach and artistic and scientific collaboration,” Shipman said. “I want to connect people who are interested in pushing the boundaries of technology for art and science collaboration."

The presentation relies on a combination of satellite imagery and data to show different aspects of the fires. Wildfires can be observed in imagery, using tools like Google Earth, but it’s harder to see small-scale features, especially under the smoke. To illustrate this, Webley put together data at near and shortwave infrared wavelengths from publicly available satellite data that shows thermal activity.

By changing the colors that represent different wavelengths, audiences can see not only the active edge of fires, but also where they have burned and their effects on the landscape.

As the images of the fire change, so does the music. It speeds up when fires rage and slows as the ground smolders.

“I thought about the cycle of destruction and renewal that happens during and after a forest fire,” Adams said of his composition. “In the beginning of the piece, it is calm and serene, and, in the middle, it is intense, while the fire is tumultuous and destructive. Once the fire has died down, then the music turns to joy, signaling the forest's rebirth and new growth.”

The team is also using the process to think about how scientists can present data and the impact that a musical score can have on how the public experiences data. Webley and his co-authors want not only to show the audience how interesting satellite data is but also to inspire them to seek more data.

“It’s not just simply looking at an image and walking away. Its thinking about the hazard itself, how the musical piece draws the person in,” he said. “It’s really about the experience."

To see the team’s final product on YouTube, click here.