Crystals help volcanoes cope with pressure

July 10, 2017

Meghan Murphy

907-474-7541

University of Alaska Fairbanks researchers have discovered that volcanoes have a unique way of dealing with pressure — through crystals.

According to a new study published in the Journal of Geology, a network of microscopic crystals can lessen the internal pressure of rising magma and reduce the explosiveness of eruptions.

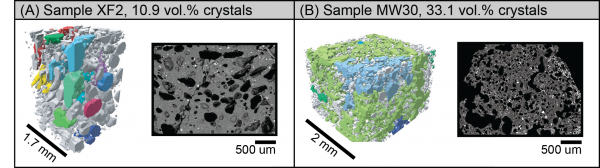

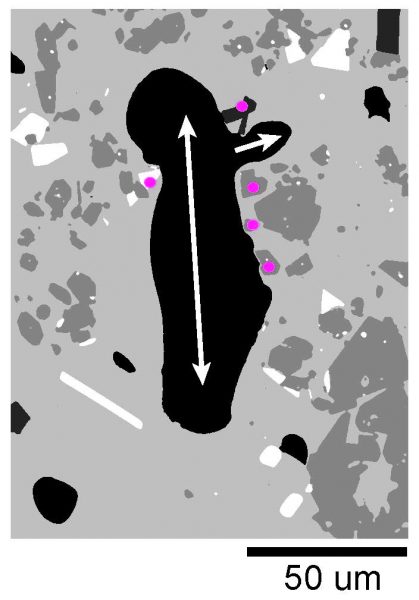

Crystals can form in the rising molten rock in as little as 18 minutes. If the magma becomes more than 20 percent crystals, they can act like guard rails that funnel gas to possible cracks within the volcano or to the opening at the Earth’s surface.

“The problem is when the gas can't get out,” said Amanda Lindoo, lead author and UAF geosciences doctoral student. “That causes a buildup in pressure that can lead to the very explosive eruptions that shoot ash plumes. The crystals can alleviate that.”

Co-author Jessica Larsen, a volcanologist with the UAF Geophysical Institute, said the findings challenge the prevailing assumption that the amount of silica in magma is the major driver in gas escape.

The usual rule of thumb, she said, is that magmas with lots of silica are slow-moving, which can make it hard for gas to escape. While scientists know that these magmas tend to form fewer crystals, she said not much research has focused on the crystal’s role in eruptions.

Volcanoes in the Aleutian Islands, the Cascade Range and Central America aroused Larsen’s curiosity. Some volcanoes in those regions have magma consistently high in silica, while others have low-silica magma.

“If you follow the rule of thumb, then the volcanoes with low-silica magma shouldn’t produce hazardous, explosive eruptions,” she said. “And yet they do. We wanted to know what was swinging the pendulum, because it’s important to understanding the hazards of eruptions.”

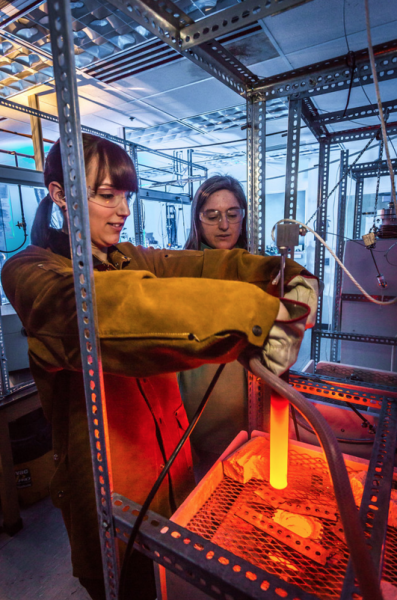

To study the crystals, Lindoo worked with Larsen in the Geophysical Institute’s Experimental Petrology Lab, which has a furnace that can superheat volcanic rocks up to 2,400 F and melt them back into molten lava. It also has pressurizing pumps, pressure lines and valves.

Lindoo created magma from eruptive materials from the Aleutian Islands. She applied extreme pressure to the magma to simulate pressures in the Earth, but then reduced pressure to mimic the way low-silica magma rises.

As the magma “rose,” dissolved water formed into gas bubbles — much as bubbles form when opening a bottle of pressurized soda. Crystals also grew in the molten part. Lindoo then compared lab samples to those taken from volcanic explosions and found patterns of crystal networks channeling gas where crystal formation was high.

Larsen said temperature, the amount of water in the magma and the speed of the magma's rise all play a role in crystal formation.

“For awhile we’ve understood how crystals form,” said Larsen. “But we didn’t know how profoundly the crystals influenced gas escape.”

Larsen said she will continue the research, but the next phase will look at how the different sizes and shapes of crystals influence gas escape.

The researchers collaborated with scientists at the University of Bristol in the United Kingdom. The National Science Foundation funded the study.

ADDITIONAL CONTACTS: Amanda Lindoo at 630-674-3889 or alindoo@alaska.edu. Jessica Larsen, jflarsen@alaska.edu.

NOTE TO EDITORS: Email Meghan Murphy at mmmurphy3@alaska.edu for the full paper. An abstract is available online at bit.ly/volcano_crystals.