New UAF wilderness program carries on tradition of empowering girls

October 27, 2017

Meghan Murphy and Nate Bauer

907-474-7541

Download text and photo captions here.

There was something different about Betye Arrastia-Nowak. Her parents were sure of it.

Just a week and a half prior, the rising high school junior boarded her first plane. Nervous about meeting a new group of people and traveling with them on a wilderness expedition into Alaska’s fjords, she flew from upstate New York to Alaska.

Yet when Arrastia-Nowak came back, she felt different and it showed.

“When my mom first saw me, she was crying because she thought how beautiful I looked because I looked so confident in myself,” she said. “I was walking through the airport like, ‘I’m Betye!’"

Arrastia-Nowak attended a new program this year called Girls in Icy Fjords, which is a tuition-free wilderness expedition at the University of Alaska Fairbanks where high school girls use science and art to explore Alaska's coastal landscape. The program aims to inspire girls to consider careers in science, technology, engineering and mathematics and build their confidence to succeed in male-dominated fields.

Claudine Hauri, a chemical oceanographer with UAF’s International Arctic Research Center, founded the program.

“We looked for girls that might not have this opportunity otherwise,” she said. “We weren’t looking for the best grades. We were looking for girls who are curious and thirsty for such an opportunity, but might need help to make it real.”

Nine girls comprised the team, hailing from all over the United States and the world, including a rural village in India and the most densely populated borough in New York City — Manhattan. They represented different ethnicities, cultures and geographies, which became the topic of late-night conversations.

“It was three girls in a tent, and I remember one night that we were lying down, all looking at the top of the tent and started to talk about school and our lives,” said Caitlynn Hanna, who lives in Anchorage and has strong ties to her Inupiaq heritage. “It was just a heart-to-heart with everyone as we were going to sleep.”

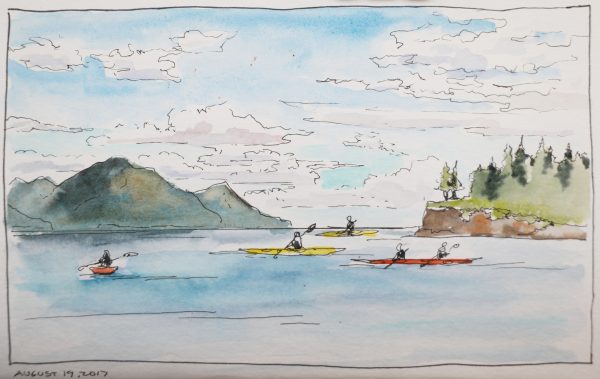

She said the relaxed bedtime conversation contrasted with the fast-paced excitement of the day. The expedition began near Bear Glacier, where the girls set up base camp. The first two days included practicing field-science observational skills, mentally and physically preparing for a kayaking expedition and gearing up in dry suits to swim Resurrection Bay.

Focus areas included glacier-ocean interaction, ocean acidification, climate change and local wildlife. Besides instructor-inspired activities, the girls asked their own science questions, designed a data sampling plan and carried out their own science projects in teams of three. The Icy Fjords team also focused on using art to make observations, express their ideas and communicate science. Evening discussions included topics such as the role of women in traditionally male-dominated fields and how emotional intelligence influences leadership skills.

The girls also learned how to work with and not against the elements.

“We were lucky to put up and break down camp in the sun,” Hauri said. “Other than that, we were fighting the rain with good spirits most of the time. At the end of the trip, we spent two days paddling 16 miles back to Seward. We are all very proud of this big achievement!”

Back in Seward, Girls in Icy Fjords wrapped up the program by spending two days at the Alaska Sealife Center, where the team gave public presentations about the trip and each of the girls’ science projects.

Hauri modeled the program after the highly successful Girls on Ice Cascades and Girls on Ice Alaska programs. Pettit founded the Cascades program in 1999 while a graduate student at the University of Washington, and UAF graduate students founded the Alaska one in 2012. More than 300 girls have participated in all three programs since then.

“Feedback from the girls, over months to years after their experience with us, shows us that connecting science to art and wilderness travel not only brings science to life for each of them but also builds their confidence and courage to push themselves," Pettit said. "Our society continues to underestimate the ability of girls — in science, in wilderness travel and other activities — and we want to show these girls and society that they can accomplish amazing things if given the chance.”

Pettit, a professor with UAF’s College of Natural Science and Mathematics, said that she also hopes the program gives girls from various social and economic backgrounds, who choose to go into STEM careers, the confidence that they can succeed in fields that don’t have a high representation of women and people of color.

According to the National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics, while white males represent one-third of the United States population, they represent half of the science and engineering workforce. In all racial and ethnic groups, more men than women work in science and engineering occupations.

Many program alumni have pursued science careers, Pettit said, while others have become artists or entered other fields. Yet they are all able to integrate science into their decision making and perspective on the world.

The three programs are all under the umbrella of Inspiring Girls Expeditions, which is a collaborative network of scientists and volunteers who support the programs and are starting new ones around the United States and the world.

Donations, grants and volunteers make all the programs possible. A National Science Foundation grant helped launch Girls in Icy Fjords.

Autumn Fry-Walkem, a Girls on Ice Alaska participant this summer from British Columbia, said that there is also something else that makes all these programs possible — courage.

“It took courage to take action on what we wanted, not knowing what would happen. It took courage to challenge ourselves in so many new ways on this expedition,” she said. “Confidence came after learning we could do these amazing things.”

The programs will begin accepting applications in December. For more information go to http://www.inspiringgirls.org/.