Preparing Alaska's communities for a tsunami

August 3, 2017

Sue Mitchell

907-474-5823

University of Alaska Fairbanks researchers recently gave Juneau and Sitka new information about what ocean waters near these Southeast Alaska communities might do during a tsunami.

The information came from UAF Geophysical Institute tsunami modelers Elena Suleimani and Dmitry Nicolsky. They're working to provide inundation maps and other information to the 60 to 70 Alaska communities that could be hit by tsunamis. The new maps take into account ocean currents that can cause water surges in harbors and other areas, sometimes hours after the first tsunami hits.

After the 2011 Tohoku earthquake quake in Japan, a wave hit Santa Cruz, California. Afterward people came back to the harbor, but hours later water surged into the harbor again, causing an estimated $10 million in damage to the infrastructure at Santa Cruz Harbor and an additional $4 million in damaged or destroyed boats. That event prompted officials to look more closely at the effect of ocean currents on tsunami inundation.

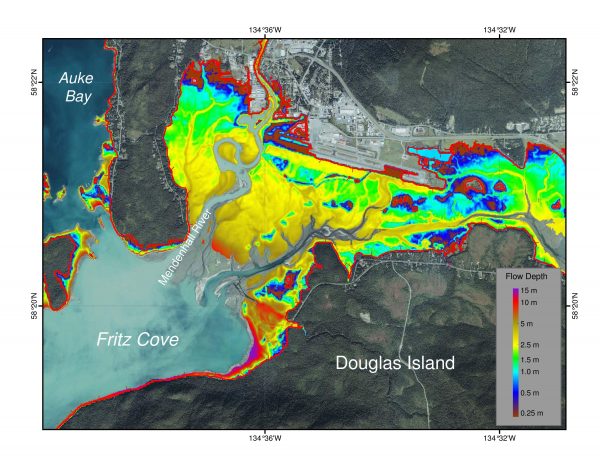

Inundation maps show how a tsunami would interact with the land and where the water would go. Simply put, “I’m seeing how far a tsunami can go inland,” Nicolsky said.

Suleimani and Nicolsky delivered draft inundation maps to Juneau. They also gave Sitka plots displaying maximum tsunami currents in its harbor. During a trip to deliver the maps, they also gave presentations about tsunamis and what to do if one happens.

Multiple waves can hit the shore for up to 24 hours, Suleimani said. The first wave is not always the biggest.

People should know where to go to escape a tsunami and the fastest way to get there.

“You might have 10 minutes. Don’t waste any time. You take your emergency kit and run,” Suleimani said.

The National Tsunami Hazard Mitigation Program started in 1996. Alaska was one of the first five states to get involved with the program. In 1998, Suleimani had just finished her master’s degree and she was hired to work on the project for Alaska. Since then, the Geophysical Institute has been providing communities around Alaska with inundation maps to prepare them for tsunamis.

Emergency managers around the state work with Nicolsky and Suleimani to determine tsunami threat levels and decide which communities are at greater risk.

ADDITIONAL CONTACTS: Dmitry Nicolsky, (907) 474-7397, djnicolsky@alaska.edu; Elena Sulemani, (907) 474-7997, ensuleimani@alaska.edu