Project helps researchers use 'trapped' museum collection

March 13, 2018

Lauren Frisch

907-474-5350

Download text and photo captions here.

A few years ago, finding a sample in the University of Alaska Museum of the North invertebrate collection was like searching for a book in an unorganized library.

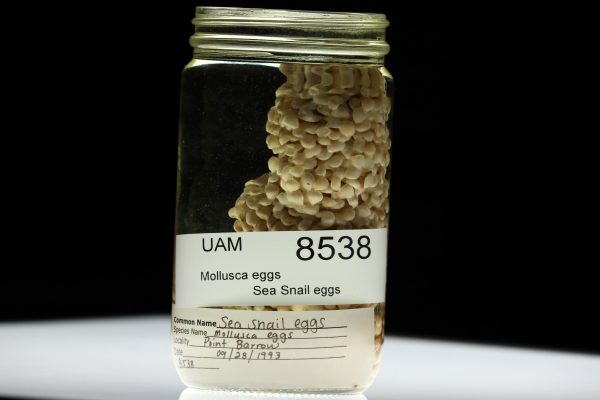

The shelves of the museum’s collection rooms were bursting with thousands of large and small jars of formaldehyde-soaked creatures and their shells from all over Alaska, but there was no way to locate specific samples.

Now, thanks to a dedicated research team from the museum and the University of Alaska Fairbanks College of Fisheries and Ocean Sciences, that collection is organized and available for researchers around the world to explore and use.

The museum has been building its marine invertebrate collection since the 1960s. But without digital records linked to specimens in the collection, it was nearly impossible for researchers to access this valuable resource. The UAF research team has spent the last two years creating a database of records for the collection, thanks to funding from the National Science Foundation.

“We are thrilled to be able to share our specimens and the information that was trapped alongside them,” said Andrés López, a researcher at CFOS and curator of fishes at the museum. “Now that this information is on the web, anyone around the world who is interested can get access to our specimens.”

Marine invertebrates are animals without a backbone or spine that live in the ocean. Some marine invertebrates like mollusks and crabs have protective shells or exoskeletons. Others, such as jellyfish, have soft, gooey bodies. Shells and exoskeletons in the museum’s collection are cleaned to remove soft tissues and then prepared and stored dry. Soft specimens are fixed in formaldehyde or preserved in alcohol and stored in bottles filled with the preservative.

In the past, museum collections like this one have mostly been used for taxonomic work — to understand and document the anatomy, variability and distribution of different species. López said researchers now are increasingly using vast museum collections for an expanding range of scientific purposes, from genetic and isotope work to larger-scale ecological studies.

CFOS graduate student Angela Gastaldi said the database maps each specimen record by species type, location and date collected. Having these three pieces of information available for each of the species in the collection can be a useful tool for those studying how species distributions are changing.

Last summer, a visitor borrowed a set of bivalves, which are mollusks with a hinged shell, such as oysters, clams and mussels, to study how their ranges have changed over time. Another group used the same bivalve set to create 3-D high-resolution scans, which they used to study how shell shapes are evolving.

“The actual records of the specimens give a snapshot of where a species existed at a certain time in history,” Gastaldi said. “Our database allows people to sort through records and look at them on a map to compare different features, species and periods of time. The record could be an invaluable tool for ecologists studying a range of marine invertebrates.”

Gastaldi played a key role in the digitization of the invertebrate records. When she first started this project with López and CFOS researcher Sarah Hardy, they were working with an unsorted room housing about 30,000 specimens.

The wet and dry collections are stored in the museum's lower level. The collection rooms are filled with large shelves that are lined with preserved specimens.

Books in a library are easy to find because they are organized by sections and given individual reference numbers. Prior to digitization, the marine invertebrate collection did not have any organizational system. “It took us a few months just to wrap our heads around the enormous amount of data and specimens we had available,” Gastaldi said.

While many of the samples had been preserved with species identification, date and location written on a label, others had unique labeling systems linked with various research expeditions. When the information was not immediately available, the research team had to spend additional time going through logbooks and data sets in order to fill in the missing details.

Now the team can digitize hundreds of species per week. About 20,000 of the museum’s marine invertebrate specimens have been sorted and digitized. The goal is to complete the process by this May.

Researchers can borrow these specimens for a variety of purposes. All requests go through the curator, who evaluates the level of possible damage that could be done to the specimen relative to the information expected to be learned from the proposed work.

“It is the job of the curator of the collection to preserve the long-term integrity of the specimen and the collection above almost anything else, even if it’s a super-cool research question,” López said. “The specimen’s value is much greater if it’s kept intact, partly because we cannot anticipate what insights future technology may uncover from properly preserved specimens.”

The process of digitizing these samples relied on help from a team of undergraduate students in fisheries, biology and natural resource management.

“One other goal of this project was to give undergraduates opportunity to gain experience working in museum collections and doing research,” Gastaldi said. It is great to help them learn new things about our project, and we definitely benefit from their enthusiasm and excitement.”

More information about the marine invertebrate database is available at www.uaf.edu/cfos/research/invertebrate-collection.