Researchers uncover some mysteries of Arctic lampreys

June 27, 2016

Lauren Frisch

907-474-5022

If you live in Fairbanks, you may recall the excitement that spread when flying lampreys made national news in June 2015. The lampreys had been dropped by gulls into parking

lots around town.

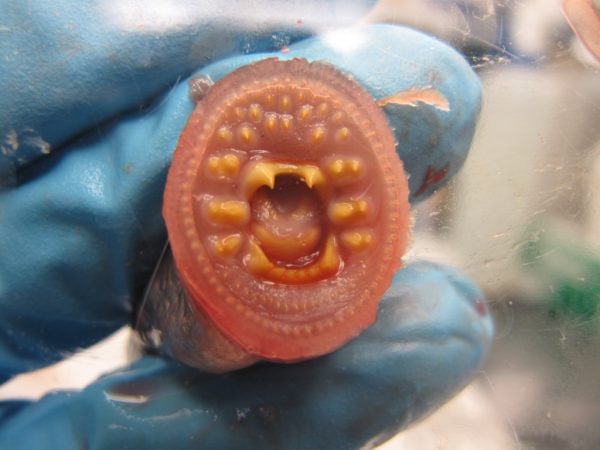

The fish are abundant in Interior Alaska waters. But little is known about how they live, eat and function as a part of the Arctic ecosystem. With limited information and funding available, University of Alaska Fairbanks researchers are trying to piece together basic information about lamprey population dynamics and diet.

Trent Sutton, a professor at the UAF School of Fisheries and Ocean Sciences, started studying Alaska’s lampreys in 2010. He joined forces with Andrés López, a professor at SFOS and the curator of fishes at the UA Museum of the North, and SFOS graduate student Katie Shink to study how lampreys develop and what this means for migration and feeding behavior.

Larval lampreys — called ammocoetes — can develop into one of two life stages. Anadromous Arctic lampreys migrate out to the Bering Sea to feed. Like salmon, they spend a number of years in the ocean, and then return to freshwater to spawn and die. Ammocoetes that develop into Alaskan brook lampreys remain in freshwater, where they become non-feeding adults that spawn and die.

Recent research suggests that Arctic lampreys and Alaskan brook lampreys are different forms of the same species. “The big question I want to figure out is — when is that decision point when a lamprey is compelled to either migrate out to the Bering Sea or remain in its natal location and begin the spawning process?” Sutton said.

With funding from the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, Rasmuson Fisheries Research Center and the UAF Center for Global Change Student Research Grant Competition, the researchers are beginning to piece together information on the lamprey’s genetic history.

Shink identified statistically distinct genetic populations of lampreys in the Chena, Gisasa and Andreafsky rivers. The scientists do not yet know why the three populations are unique. The Chena and Gisasa respectively feed the Tanana and Koyukuk rivers, major tributaries of the middle Yukon River. The Andreafsky is one of the final rivers to join the lower Yukon before it flows into the Bering Sea.

The researchers are also studying lamprey feeding habits. It is commonly assumed that all lampreys are parasitic, meaning they attach to a host and consume their blood. Shink discovered fish bones and fins in Arctic lamprey intestines, suggesting the fish are actually predators. She is the first researcher to study the diets of Arctic lampreys from samples of intestinal tract contents.

Shink is using environmental DNA testing to identify species present in lamprey intestines. Her samples were collected during annual National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration trawl surveys.

The researchers found DNA for salmon, cod, flatfish, capelin and rainbow smelt. Unexpectedly, they also detected a mystery: DNA sequences for sandlance, a small, agile fish that Shink believes is much too quick to be susceptible to predation by a lamprey.

“That’s one of the challenges of this genetic technique — determining how our results make sense, and in what context,” Shink said.

There are still many unknowns about how lampreys develop and function. The research team is eager to continue unraveling the story.

Read more on the School of Fisheries and Ocean Sciences website.