To UAF oceanographer Hauri, communication matters

November 30, 2016

Nate Bauer

907-474-7413

Download text and photo captions here.

Claudine Hauri, a researcher at the University of Alaska Fairbanks’ International Arctic Research Center, recognizes the struggle to communicate about complex scientific concepts. Take, for example, “ocean acidification.”

“That’s the simplest way we’ve found for talking about the issue,” she said, “and even that term has big problems. Strictly speaking, the ocean will never be wholly acidic. The consequences of that are tough to imagine.”

The issue focuses on the chemical makeup of the world’s oceans, which has far-reaching implications, especially for Alaska marine wildlife and the food web they inhabit. This chemical balance — and the kinds of microscopic conditions and resources it enables — determines what kinds of animals can live in the sea.

Even very small changes can have huge effects.

“Chemical changes in the ocean affect the building blocks of ocean life,” Hauri said. “Little sea snails, for example, are a major food source for birds and whales and fish, and they make their shells from calcified ocean carbonates. That shell-making process is more challenging if the chemical balance changes.”

Hauri’s been an expert in chemical oceanography for years, though she’s been focused on the topic of what goes on under the sea for much longer. As a youngster and even through parts of graduate school, her passion was marine biology.

“I just really loved dolphins and whales,” she said.

But it was during a research project in Australia’s Great Barrier Reef when she learned how macroalgae could affect the conditions for coral, including the water’s pH levels. She became fascinated with the ocean’s inorganic carbon cycle and studying differences between the past, before human activity was contributing to high levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide, and today.

Hauri has been at UAF since 2012, starting as a postdoctoral researcher at the Institute of Marine Science. She was appointed a research professor at UAF’s International Arctic Research Center last year.

Hauri noted that communicating with the public about the topic can be tricky. Conveying the seriousness of the problem, which has the potential to kill off portions of fishing resources on which Alaska depends, is important. This is why a term like “ocean acidification” can be effective.

“People hear ‘acidification’ and they can grasp that it’s dangerous,” she said. “People recognize that balance on the pH scale is important to maintain.”

For an oceanographer, however, accuracy and precision are equally important.

“The shifts in CO2 we’re talking about would not be harmful or noticeable for a person taking a swim,” Hauri said. “But every species and organism has a set of conditions within which they can flourish — I call it their survival envelope.”

For some levels of the marine food web, chemical changes in the ocean challenge the bounds of that envelope. “It’s like for us—just because one individual person can withstand some difficult conditions doesn’t mean it won’t make many or most of us very sick or weak,” she said. “And that can mean very bad things for a whole species.”

For the networked systems of the climate and the ocean, the notion of a “root cause” is another term that’s faulty and complex. These systems are largely series of interconnected feedbacks, Hauri explained. Increasing levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide, higher temperatures, changing sea ice content, melting glaciers, more freshwater and precipitation, shifting chemical composition of the ocean — all of these have the potential to multiply and contribute further change to other climate components.

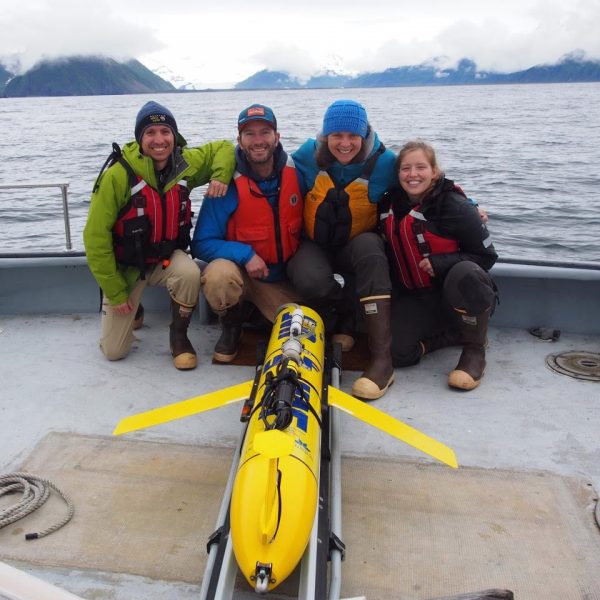

To understand these complexities, and the practical effects they may have for our fisheries and food supplies, Hauri employs a wide range of innovative techniques, including sea-based moorings, autonomous carbon dioxide-measuring gliders and ocean modeling.

She also works to ensure new generations and groups of young scientists are moved to pick up and continue this type of creative scientific work. For years she has participated as a leader in Girls on Ice, a tuition-free wilderness program for high school girls, a demographic that is underrepresented in the sciences.

In 2017 the program (now known as Inspiring Girls Expeditions) will offer its first Girls in Icy Fjords trips to Bear Glacier in Seward, where participants will learn about the important systematic links between glaciers and oceans.

For Hauri, again, it’s about connections.

“Education, awareness, excitement about science — they should all start early. Getting connected to nature is very important, very early on,” she said.

“This is a chance to inspire young people who wouldn’t otherwise have the chance to experience the outdoors, to act as role models, to raise self-confidence. It’s fulfilling.”